“Dude, you’re TOTALLY wrong. ‘Halloween’ (1978) NEVER sets out to prove if ‘the boogyman’ exists or not. Michael Myers is simply referred to as the ‘boogyman’ a couple of times because he is so demonic and creepy. The central question of ‘Halloween’ (1978) isn’t, does the boogieman exist, it’s can Laurie Strode Survive the night with this crazed person, relentlessly stalking her.“ [sic]

– Self-described pre-pro screenwriter. 16 spec scripts written.

“You’re confusing plot with theme.”

– Me

Don’t cry. We’re here once again to exorcise bad story analysis!

Does the boogeyman exist?

Ah… the interweb. A place where people from all walks of life come together to discuss things and, unfortunately, sometimes find themselves tangled up in bad movie analysis. These bad analyses by people attempting to find success in screenwriting are probably indicative of why their work hasn’t reached the level they aspire to; they’re often more likely to be blinded to structural and thematic issues within their own work more than that of others. If they can’t get elements of a well-known movie correct, it wouldn’t be surprising to find similar issues within their own work (nor to find the same mistakes made in all 16 of their scripts.)

But let’s not digress.

John Carpenter’s Halloween is a story worth digging into to see what separates it from many of its contemporaries and predecessors. Though it’s a simple story well told, its theme postulating whether the boogeyman actually exists is the one narrative factor that elevates the story from a low-budget, b-story slasher film to a full-blown classic.

The Importance of Perspective

Despite the holiday’s supernatural connotation, the story of Halloween itself is set in the natural world. In other words, the laws of “reality” apply, which gives the film a sense of realism. This, in turn, helps to filter the lens through which each character sees the events. As a result, and much in the same way, the thematic arguments are made in The Shawshank Redemption via the use of setting, events, and character perspectives, the notion of the boogeyman balances toward non-existence through the eyes of adults to make the denouement all the more powerful and haunting. After all, the definition of the boogeyman (aka “bogeyman”) is “a monstrous imaginary figure used in threatening children.”

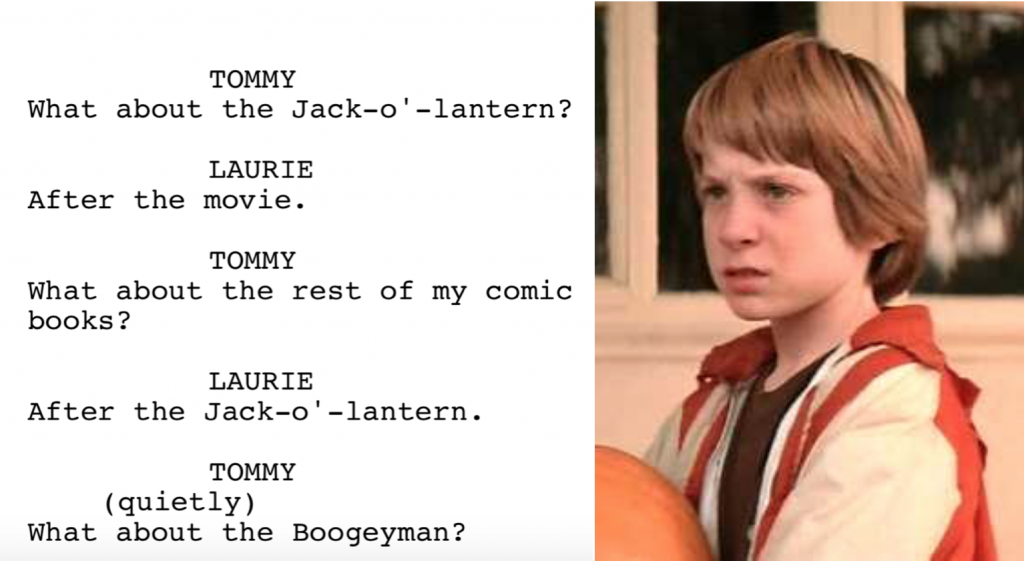

As the argument for the boogeyman’s existence is made throughout the story, it’s set up and acknowledged primarily through the eyes of eight-year-old Tommy Doyle. Early in the story, Tommy is teased into believing, “he’s going to get you, he’s going to get you… the boogeyman is coming!” When Tommy later sees Michael carrying Annie’s body outside, he makes an association between Michael and the boogeyman.

The audience, however, knowing the boogeyman is just an imaginary figure referenced by adults in order to make children behave is meant to skew their reading away from Tommy’s perception. Instead, their interpretation is more likely to be as intended by the author: we’re seeing through the eyes of an eight-year-old who’s been influenced by an earlier taunting at school.

Tommy Doyle’s the first person to believe in the boogeyman.

Despite its setting in the ordinary (natural) world, Halloween subtlety introduces elements of the super-natural early on. One such supernatural element, Michael’s ability to drive a car after years of institutionalization, is explored in film critic Robin Wood’s essay entitled “An Introduction to the American Horror Film”:

The basic premise of the action is that Laurie is the killer’s real quarry throughout (the other girls mere distractions en route), because she is for him the reincarnation of the sister he murdered as a child (he first sees her in relation to a little boy who resembles him as he was then, and becomes fixated on her from that moment). This compulsion to reenact the childhood crimes keeps Michael tied at least to the possibility of psychoanalytical explanation, thereby suggesting that Donald Pleasence may be wrong. If we accept that, then one tantalizing unresolved detail becomes crucial: the question of how Michael learned to drive a car. There are only two possible explanations: either he is the Devil, possessed of supernatural powers; or he has not spent the last nine years (as Pleasence would have us believe) sitting staring blackly at a wall meditating further horrors.

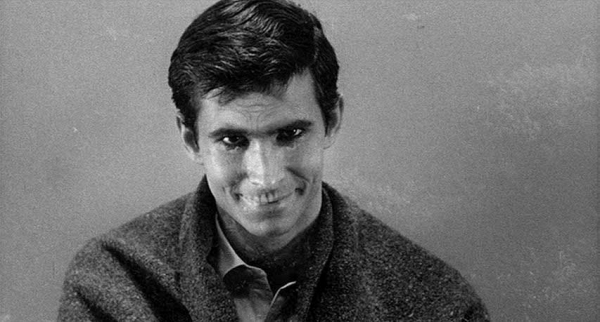

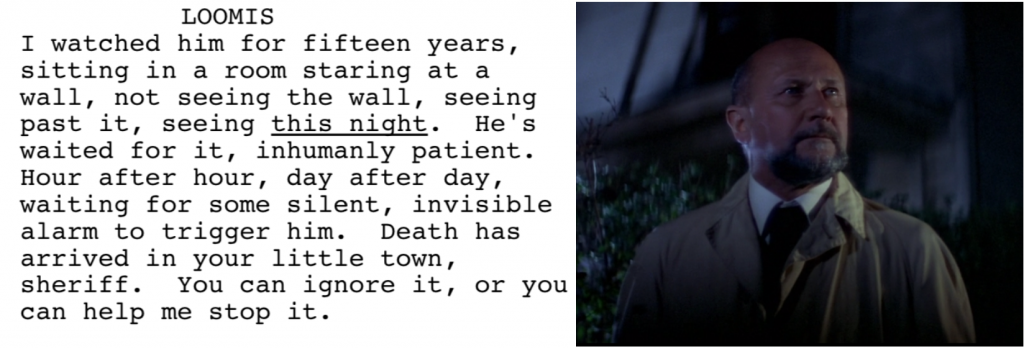

This, of course, is ultimately left unresolved, but it does illustrate Dr. Loomis’s perspective and subjective reading of Michael. His reference to Michael as “it” instead of “him” and his continual referencing of Michael as the devil or having “the devil’s eyes” demonstrates his personal perspective.

Loomis is, in essence, the antithesis of The Exorcist‘s Father Karras. Whereas Karras is a priest who favors psychology for finding answers to a supernatural situation, Loomis is a psychiatrist who comes to a supernatural conclusion regarding Michael’s inexplicable behavior:

Dr. Loomis’s analysis sounds a bit extreme to Sheriff Brackett and the audience.

While Loomis is an authority figure in the film, to the audience, his perspective comes across as somewhat unreliable – yet they are dependent on it, for the story doesn’t encompass Michael’s years of institutionalization. Loomis is, after all, a psychiatrist, but his obsessive drive, fear-mongering, and associating Michael with “evil” and “the Devil” make him appear as equally unhinged and deranged as Michael in some regards. The events that the audience has been privy to thus far, e.g., Judith Myers’ slaying without motivation, suggest Michael is nothing more than a murderer, which, at the very most, puts him squarely in the realm of the “natural” world and not within the context a psychiatrist would discuss. Such cognitive dissonance is one of the factors that helps build and maintain the story’s suspense.

The function of the Main Character

As with films like The Shawshank Redemption and Sicario, Halloween’s main character isn’t the story’s protagonist. Laurie Strode is, however, the character the audience identifies with most and sees the events through. And like the aforementioned films, her perspective is built around what the film’s authors ultimately want to convey to its audience.

Laurie, at seventeen years of age, is too old to believe in the boogeyman. She’s an ordinary girl in a seemingly ordinary world with no inclination whatsoever that “the shape” stalking her is the boogeyman. In fact, she fulfills the role of the story’s skeptic, flat-out disbelieving in its existence:

Laurie’s perspective is in direct conflict with Tommy’s.

By placing the audience in Laurie’s shoes as the main character, we identify with her as we, too, know there is no such thing as the boogeyman. Well, most of us, at least. Because the story is based in the natural world, the elements that happen in the plot throughout the story ultimately help to shape the story’s theme towards the supernatural explanation of the boogeyman’s existence.

When Laurie first sees Michael, of whose persona she is totally unaware, it’s always from a distance and with fleeting glimpses… and then he’s gone. For all she knows, the man stalking her is Ben Tramer, the boy she tells Annie she would rather go to the dance with. Nevertheless, Laurie’s first physical encounter with Michael results in her stabbing him with a crochet needle. The subsequent encounter results in stabbing him in the eye with a hanger and then in the chest with the knife.

Because the setting is in the natural world, we expect the natural law of order to exist as a result of each subsequent attack on Michael, afflicting more and more damage. But as Tommy states, “You can’t kill the boogeyman.”

At the story’s climax, Michael once again attacks Laurie. This time, Dr. Loomis is there to shoot Michael. Not once. Not twice. SIX times! As Michael falls from the second-story balcony, he’s presumed dead, as shown in the objective view from the overhead of his motionless body on the ground.

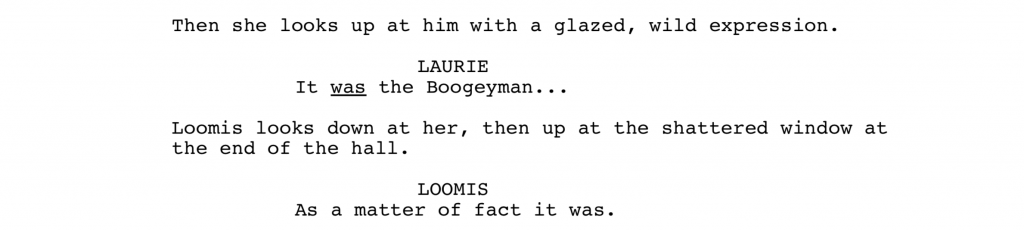

Surely, an ordinary man in an ordinary world would be dead from this act alone, not to mention from accumulated previous wounds, too. But being the climax, this is where the story’s theme from the central argument it proposes resonates. The final dialogue between Dr. Loomis and Laurie shows her perspective has changed as she identifies Michael as “The Boogeyman.” Dr. Loomis agrees; however, both reference Michael as such in the past tense.

Laurie’s perspective has been changed by the events of the PLOT, resulting in the validation of its central question and its THEME.

The Audience’s Perception and Reception

A change in perspective isn’t always enough to satisfy an audience. In the case of Halloween, the POV shot from Loomis looking at the barren ground where Michael landed is what validates the author’s position on the subject of the boogeyman’s existence. Dramatica‘s theory of story refers to this as “Author’s Proof”:

Technically speaking, the moment of climax in a story is the intersecting point where the nature of the Main Character crosses paths with the nature of the Overall (Objective) story. The purpose is simply to illustrate that the suspected effect of the climax has or has not truly resulted in a change in course. As such, it functions as the Author’s Proof and is a key component of the denouement.

If nothing else, it’s essential to understand this bit of story structure and how it plays into the film’s climax and theme. It is the climax itself that determines whether the main character changes or remains steadfast in their beliefs. The climax is a culmination of the story’s argument to that point, and to that point, the highest degree of pressure is put on the main character to change or remain steadfast.

If the main character is to remain steadfast in their beliefs, it will most likely resort to changing someone else around them or the film, resulting in tragedy. Either way, the climax is where the theme is found. The story’s events and their plotting are merely the dramatic exploration of the various perspectives at play that mold and shape the theme. How the two are combined shapes an audience’s reception. This is why storytelling has, at least in the hands of those who do it well, the power to influence and change lives.

In the case of John Carpenter’s Halloween, the audio clip of the ending of an audience’s reaction synced to the film back during a 1979 show demonstrates how the film’s theme, as determined by the climax, was ultimately received:

John Carpenter’s Halloween ultimately delivers a suspenseful and well-constructed, if not altogether simple, story that has chilled audiences and critics alike for forty years now.

One final note about audience reception and film analysis

When a story (or film) is analyzed, it’s done in its totality, considering all that encompasses it. This incorporates a posteriori knowledge of the film’s events, themes, characters, setting, etc., to come to some conclusion about the work. An audience’s reception and appreciation, however, is linear: the events unfold with the greater meaning to be discovered at the end. This is an important distinction to note because oftentimes, people will prescribe a posteriori knowledge to the story when the audience has, in fact, not experienced the events, nor do they have knowledge of specific information. Subsequently, they cannot arrive at the same conclusion at that particular point in time while in the midst of their experiencing the story.

Such is the case with John Carpenter’s Halloween. 40 years since its release, it’s easy to forget the experience of seeing the film for the very first time. After myriads of clones, sequels, and reboots, most, if not all of which fail to capture the spirit of the original, Michael Myers has become synonymous with “the boogeyman.” The first-time experience of watching him become the embodiment of a myth has become akin to letting the cat out of the bag: once it’s done, it’s hard to put it back in. This, perhaps above all else, is why John Carpenter has said when sitting down to write Halloween 2, there simply was no story to tell.

Further to this point, the recent Halloween reboots have once again strayed from what made the first film work to the point that, as problematic with its many original sequels, each attempt to explain, justify, show, rationalize, etc., a situation regarding Michael only serves as an injustice to the original story in and a “demystifying” of what made it work. The writers and producers would be of great benefit to allowing the most powerful tool to fill in the blanks, that being the imaginations of each individual audience member.

Written By: James P. Barker

This article was originally posted here.